Surgical fusion for spinal stenosis is never a primary treatment modality used to correct central canal narrowing, but is often integrated into other curative procedures when operative damage to the backbone creates instability in the vertebral column. Virtually all approaches to spinal stenosis surgery access the interior of the spinal canal and might remove large sections of the vertebral bodies in order to clear the stenotic regions. After immediate surgical treatment using laminectomy, discectomy or corpectomy, some patients must further undergo fusion of the operated vertebral levels, in order to reinforce the infrastructure of the spinal column. Other patients might enjoy placement of artificial intervertebral discs or spinal implants to prevent the necessity for fusion.

This essay details the use of spinal fusion in the stenosis treatment plan. We will provide a glimpse at the positive aspects of spondylodesis, but will certainly concentrate on the far more numerous negative consequences of vertebral fusion procedures.

Surgical Fusion for Spinal Stenosis Uses

Fusion surgeries are performed for many possible reasons within the back and neck pain sectors of medicine:

Fusion can be used to stabilize spondylolisthesis, to minimize hyperkyphosis or hyperlordosis, to straighten severe scoliosis and to reinforce any section of the spine that is thought to be damaged and unable to be protected from the typical stresses encountered during normal life.

In spinal stenosis patients, fusion is an add-on surgical technique, just like it is in many other procedures within the back and neck pain therapy industry. This means that fusion is not the curative component of the surgery, but instead is performed after the treatment which resolves the stenosis is complete. Vertebrae are fused in order to fill voids left in the spinal structures by the surgical treatment process.

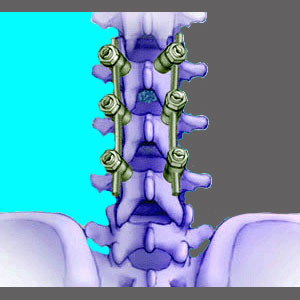

Remember that most spinal stenosis operations will remove pieces of bone and possibly entire intervertebral discs. The spine is not designed to function when left in such a state of disrepair. Fusion addresses the gaps left in the spinal infrastructure, by filling in the locations with bone grafts, bone substitutes or synthetic hardware. Vertebral bones are joined together permanently, removing any semblance of individual movement between the treated spinal levels.

In essence, the spine is repaired, not to regain lost function in the operated levels, but instead, just to maintain stability of the overall vertebral column.

Spinal Fusion Consequences

The natural design of the spine allows for each vertebra to move independently of the one below and above it. Each vertebra is cushioned and separated by an intervertebral spacer, called a disc. These soft tissues provide flexibility in what would otherwise be a solid mass of bone.

Fusion removes the disc between treated bones and joins the vertebrae together to form a mass that is more than twice the height of a usual spinal bone. This fusion allows the operated level to maintain form, yet forces it to lose functionality.

Fusion is positive since it allows many very invasive treatments to be performed on the vertebral column, while still stabilizing the spine after the trauma of surgery is complete. However, that is about where the benefits of fusion end; abruptly.

Fusion goes against the natural design of the spine and causes many negative health issues to occur in most operated patients:

Fusion increases stresses on neighboring spinal levels. This inherently leads to accelerated deterioration of the vertebral and intervertebral components of these nearby levels.

Individual spinal level functionality is drastically reduced in the operated location. This creates a predisposition towards spinal injury at the treated level.

Spinal fusion is a risky procedure in its core methodologies:

Organic bone grafts might necessitate the healing of more than one location for surgical wounds or might increase the risk of contamination from donor grafts from other patients. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that grafts will be accepted by the anatomy. Many grafts are rejected by the body, become necrotic or simply do not fuse correctly.

Substitute synthetic bone grafts involve the same risk for rejection, allergy. infection or lack of fusion.

Hardware-assisted fusions are the most dangerous of all, boasting very high failure rates based on apparatus rejection, infection, loss of spinal movement, inordinate scar tissue formation or hardware detachment. All of these issues can become catastrophic health problems.

Finally, fusion requires a terribly long and painful recuperation period that might take a year or more for full healing to occur. Even after a fusion is solid and fully healed, problems can still occur at any time in the future, especially if the operated level is exposed to stress from injury or continuing degeneration.

Alternatives to Surgical Fusion for Spinal Stenosis

For some patients, fusion might be avoidable by utilizing specialized spinal implants to maintain the stability of the vertebral column after invasive stenosis procedures. For patients with disc-related stenosis, who elect to undergo complete discectomy, substitute intervertebral discs can be utilized to restore the spine to a fully stable and functional state. However, both of these approaches are only usable in some circumstances and both still demonstrate high risks for device failure or anatomical rejection.

Better solutions for avoiding fusion involve utilizing the least invasive types of curative treatment to resolve focal areas of stenosis, without compromising the vertebral column as a whole. Many doctors are reinventing older procedures and pioneering new operations that can treat stenosis without the possibility for fusion to become a liability within the complicated therapy equation.

Spondylodesis for Spinal Stenosis Help

Spondylodesis recipients face more surgical complications than any other back or neck pain patients. They must endure the exponentially increased effects of the degenerative processes that will hasten the aging of surrounding spinal levels.

Fusion patients have the lowest chance of making through treatment with only one surgery, since immediate postoperative complications force many recipients to undergo two or more follow-up operations within a year of the original procedure.

Fusion patients are likely to require follow-up surgeries in the future, even if all goes well. This is due to the increased risk for fracture of the fused levels, the risks of hardware malfunctions and the universal incidence of accelerated deterioration of nearby levels.

For now, some patients will have no choice but to face the hazards of spondylodesis in order to cure their dire stenosis concerns. The procedure might be a necessary evil for these poor souls. However, other patients have options and that is the point of this entire article. If it is possible to avoid fusion, then do anything and everything in your power to cure your stenosis, without re-engineering your spine in the most illogical way imaginable.

Spinal Stenosis > Spinal Stenosis Surgery > Surgical Fusion for Spinal Stenosis